SEED & BREAD

Number 116

THE GREEK ALPHABET

It is cause for thanksgiving that in the providence of God the language

barrier that once stood between the common man and the truth of God has

been broken. The New Testament was written in the common Greek of the

first century, usually called koine Greek, and for centuries many of the

vital facts of divine revelation were hidden from the average man. He

had to rely on fallible human authorities in a realm where accuracy and

certainty were most vital. He had no means of verifying the correctness

of a translation. Now, all this has been changed, so that any person of

ordinary intelligence who will apply himself to the task can discover

for himself what God has actually said. All he needs to do is make use

of the tools that men of God have made available.

By "tools" I refer to such monumental works as

* Young's Analytical Concordance;

* Strong's Exhaustive Concordance;

* The Englishman's Greek Concordance by George Wigram;

* The Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament by Thayer;

* The Englishman's Greek New Testament (an interlinear by Bagster);

* The Analytical Greek Lexicon (Bagster).

The last mentioned contains an alphabetical arrangement of every

inflexion of every word in the Greek New Testament with a grammatical

analysis of each word.

However, if the student wants to use these books speedily and

effectively he must know the Greek alphabet, and be able to transpose

upon sight the Greek characters into their English equivalents. For

example, when he comes upon the word.avOpwIIo ( sorry, computer

limitations – O is Theta, II is Pi, Ed.), he should be able on sight to

change this into anthropos.

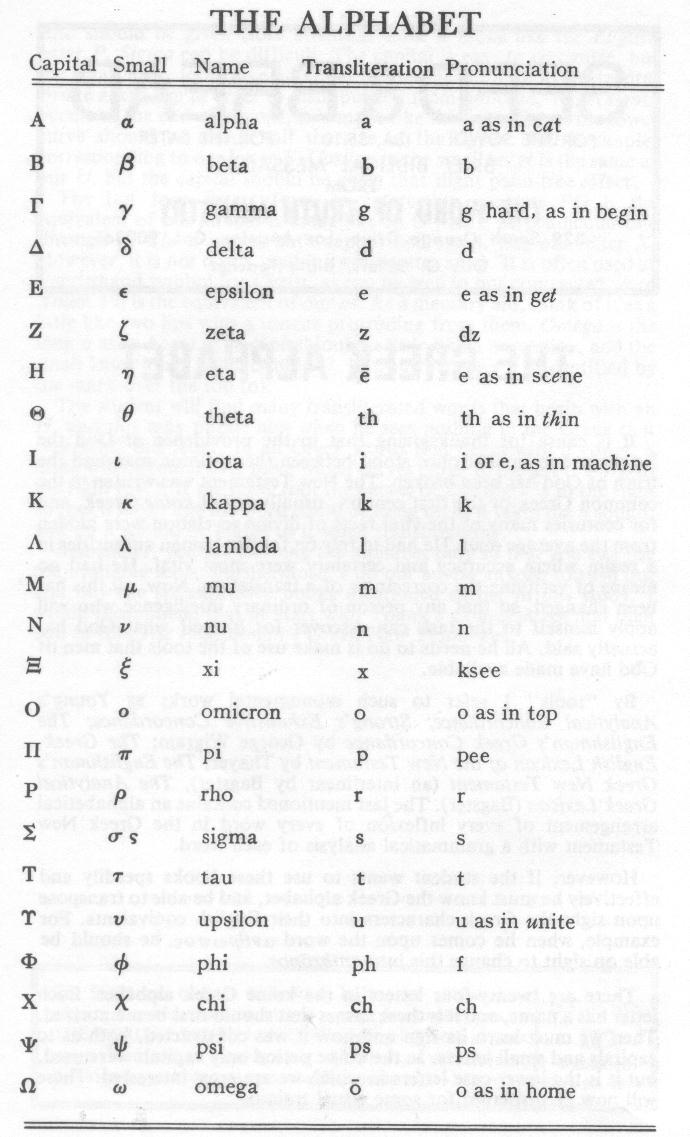

There are twenty-four letters in the koine Greek alphabet. Each letter

has a name, and it is these names that should first be memorized. Then

we must learn its sign and how it was constructed, both as to capitals

and small letters. In the koine period only capitals were used, but it

is the lower-case letters in which we are most interested. These will

now be displayed for some visual training.

There are numerous helps that will aid the student in handling the Greek

alphabet. It can be divided into six groups of four letters each,

learning the first four names, then advancing to the second group. The

first letter is named alpha. I assume every Bible student is familiar

with the passage wherein the Lord says: "I am the Alpha and Omega, the

first and the last." If so, you have the first and last letters of the

alphabet already with only twenty-two more to go. And since you are

learning the alphabet, you have the first and second letters, alpha and

beta. The third letter gamma should be easy since it is used in many

English words such as gamma-ray and gamma-globulin. The fourth letter

delta should be very easy since we have brought it into English to

describe the formation made by the mouth of a river, which is shaped

somewhat like the Greek letter 1::..Now we have alpha, beta, gamma,

delta - the first four - and omega, the last letter, so only nineteen

more to go.

The student should learn to write the Greek letters with careful

attention being given to the small ones. Alpha is made the same as our

letter a, both small and capital letters. It is pronounced aas in cat

and ah as in father. Beta is made the same as our capital B. In writing

the small letter begin with an upward stroke a little below the line.

Gamma in its capital looks like a gallows, and the small letter

resembles our y. If the top were closed it would look like our g. It is

a letter that varies in sound so when it is followed by another gamma (yy),

a kappa (YK), an xi (y_) it is pronounced as an n. Thus aggelos becomes

angelos when pronounced.

Delta is an easy letter to make. The capital is a simple triangle, but

in making the small letter be sure to get the curl at the top. Epsilon

is the short e, made the same as in English in the capital, but the

small letter is a semicircle with a horizontal mark in the middle. Zeta

is pronounced as if it had a D in front of it. In making the small

letter be sure to add the little mark on the top and the hook on the

bottom. Etais the long e. It could be somewhat confusing since the

capital is made like an H, and the small letter like an n. In making it

be sure the righthand stroke comes below the line, and in

transliterating it put a mark over it so it will not be confused with

the short e. Theta is a circle with a bar across the middle, and the

small letter is an upright oval with the same bar. Iota is the smallest

of all the characters and is used figuratively to signify something

insignificant. Kappa is easy since it is made the same as our letter K.

Lambda is pecular since the capital looks line an inverted V. An oddity

about the small letter will make it easy to remember. Notice the leaning

right-hand stroke with the little bar on the left to keep it from

falling backward. .

Muhas a long left-hand stroke, a shorter right-hand stroke, and a

sagging bridge that ties them together. Nuis the same as our N, but the

small letter looks like our v. It should be made with a slight outward

curve to the right-hand stroke. Xi (pronounced ksee) demands close

scrutiny. The capital is three horizontal lines, the middle line being a

little shorter. This is not the same as our letter X, even though it is

made like it. You can remember its distinctive character from the trade

name Xerox (Kseerox). The small letter is made like a backward number 3,

and it should have the small mark at the top and the curved tail at the

bottom, a little below the line. Omicron is the short 0 and is

pronounced as in box. Pi is familiar to all who have studied geometry,

but the pronunciation is pee, not pie. Rhoshould be given close

attention since it looks like the English letter P. Sigma can be

difficult. The capital is easy to recognize, but the small letter looks

like an 0, so it must have the short horizontal stroke at the top in

order to distinbuish it from omicron. When sigma occurs at the end of a

word, it is made like the letter S, but the lower curve should be about

half the size of the upper. Tauis simple, corresponding to our letter T.

Upsilon in the small letter is the same as our U, but the capital should

be given that slight palm-tree effect.

The last four letters form an interesting quartet. Phi is the equivalent

of our ph and is made like an 0 with a perpendicular line through it.

Chi is made, both capital and small, like our letter X. However, it is

not our X, and it transliterates as ch. It is often used as a shorthand

symbol for Christ, as can be seen in our contracted word Xmas. Psi is

the equivalent of our ps. As a memory aid, think of it as a little like

two lips with a tongue protruding from them. Omega is the long 0 as in

home. The capital looks a little like a horseshoe, and the small letter

looks like a double O. In transliterating it is identified by the mark

over the top (0).

The student will find many transliterated words that begin with an H,

and this may puzzle him when he sees nothing in the Greek that

represents this letter. In all Greek words that begin with a vowel, a

mark will be found over them which curves either to the left ( .) or to

the right ( , ). If the hook (not the curve) of this mark is to the

right so that it looks like the word could be hung on it, it takes the h

sound, and an h should be added to it when transliterating.

Remember, you are learning the alphabet only so that you can use the

available tools. Furthermore, I do not advise anyone to rush out and buy

the six expensive books mentioned earlier in this study. I would

recommend that he start with Young's Concordance and then add to this

The Englishman's Greek New Testament.

INDEX

Issue no. 117